History of the Great Unconformity Interpretive Site

Land Management Issues

There is no history of visitor services in the Frenchman Mountain-Rainbow Gardens area, which lies on federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The major recreation focus of the BLM in Southern Nevada is the Red Rock National Conservation area on the west side of Las Vegas. To the east of Rainbow Gardens lies the Lake Mead National Recreation Area (LMNRA), managed by the National Park Service. From the perspective of the Park Service, the Frenchman Mountain region is a buffer zone between the LMNRA and urban Las Vegas. Until the mid-1990s, the main public uses of the Frenchman Mountain-Rainbow Gardens area were uncontrolled target shooting, illegal dumping, and off-road vehicle use.

During the 1990s the population of the greater Las Vegas area increased by 55% to 1.3 million people, and urban sprawl began to lap at the foot of Frenchman Mountain. The encroaching population is incompatible with target shooting, which is no longer permitted in the Frenchman Mountain area. Anti-dumping laws are now much more aggressively enforced, and much of the old trash has been removed during BLM-Boy Scout-volunteer clean-up campaigns. The BLM is beginning to focus more attention on the east side of the Valley, not least because of an endemic species of bearpaw poppy (Arctomecon sp.), whose habitat is fragile and disappearing. Primarily because of the presence of this poppy, but also to protect geologic resources, in 2000 the BLM classified the Rainbow Gardens as an "area of critical environmental concern," which carries with it a measure of protection from unrestricted off-road vehicle use and other abuses.

So, however gradually, the Frenchman Mountain-Rainbow Gardens area is being reclaimed from the dumpers and plinkers, and it is slowly being transformed into a multi-purpose recreation area. Helping this process along is a non-profit citizens group called Citizens for Active Management of the Frenchman-Sunrise Area (CAM), which works with the BLM on management issues, clean-ups, and trail projects. This geologic interpretive site is the result of a loose partnership between CAM and the BLM.

Phase I - The Great Unconformity Roadside Interpretive Panels

This interpretive project began in the early 1990s as part of CAM's effort to awaken the public to potential recreational and educational attractions in the Frenchman Mountain area, and also to stimulate the BLM to devote more attention and resources to the Frenchman Mountain-Rainbow Gardens area. Tens of thousands of people pass by Frenchman Mountain every year on their way to Lake Mead, but few had any reason to stop and look at the rocks. We (the CAM Board of Directors) needed a roadside attraction that would capture the interest of passers-by and entice them to get out of their cars for a few minutes.

The Great Unconformity was the logical choice. It is located close to town, directly adjacent to Lake Mead Boulevard, and the name sounded important and somewhat mysterious. The main drawback of the site is that it is so close to the urban environment that it suffers from the urban blight of spray paint graffiti. Broken beer bottles and general trash are also recurring problems. We anticipated these problems and planned the site to be as resistant to vandalism as possible.

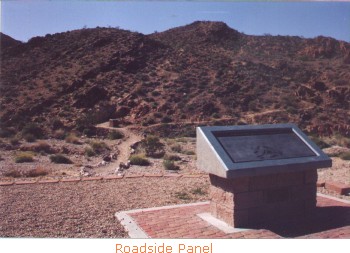

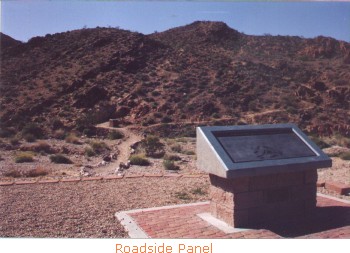

We decided to place two interpretive panels at this site. (Phase II had not yet been conceived.) One panel was located close to the road, and the other a short distance away directly adjacent to the exposure of the Great Unconformity. The panels, which were prepared by Stone Imagery of Carlsbad, California (StoneImage@earthlink.net), are coarse crystalline diorite from southern India (called "black granite" in the stone industry). The text and figures are etched into the stone. The result is a very attractive stone panel that stands up well to abuse and cleans up very well.

We decided to place two interpretive panels at this site. (Phase II had not yet been conceived.) One panel was located close to the road, and the other a short distance away directly adjacent to the exposure of the Great Unconformity. The panels, which were prepared by Stone Imagery of Carlsbad, California (StoneImage@earthlink.net), are coarse crystalline diorite from southern India (called "black granite" in the stone industry). The text and figures are etched into the stone. The result is a very attractive stone panel that stands up well to abuse and cleans up very well.

The roadside panel is inset into a tilted concrete platform mounted on a cinder block pedestal. This panel summarizes the geology of Frenchman Mountain and the Great Unconformity. Much of the text and most of the diagrams of both panels are included on this website. The stone panels were paid for with money raised by CAM from corporate sponsors and the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. A BLM crew prepared the site and built the platform and pedestal for the roadside panel. The outcrop panel was originally placed on a steel plate attached to a steel post. Vandals fairly quickly destroyed this outcrop panel, and the BLM replaced it with a new one mounted on a cinder block pillar. Unfortunately, the crew who built the new pillar apparently did not know exactly where the unconformity was located, and they didn't bother to ask. They oriented the new panel about 40º from where it should be facing. This confuses some visitors who don't know exactly where to look to see the Great Unconformity. As exemplified by the miss-alignment of the pedestal, poor communication and frequent staff turnover at BLM have been mild recurring problems in the CAM-BLM partnership. In general, however, the relationship has been friendly, efficient, and mutually supportive.

The roadside panel is inset into a tilted concrete platform mounted on a cinder block pedestal. This panel summarizes the geology of Frenchman Mountain and the Great Unconformity. Much of the text and most of the diagrams of both panels are included on this website. The stone panels were paid for with money raised by CAM from corporate sponsors and the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. A BLM crew prepared the site and built the platform and pedestal for the roadside panel. The outcrop panel was originally placed on a steel plate attached to a steel post. Vandals fairly quickly destroyed this outcrop panel, and the BLM replaced it with a new one mounted on a cinder block pillar. Unfortunately, the crew who built the new pillar apparently did not know exactly where the unconformity was located, and they didn't bother to ask. They oriented the new panel about 40º from where it should be facing. This confuses some visitors who don't know exactly where to look to see the Great Unconformity. As exemplified by the miss-alignment of the pedestal, poor communication and frequent staff turnover at BLM have been mild recurring problems in the CAM-BLM partnership. In general, however, the relationship has been friendly, efficient, and mutually supportive.

Phase I was completed in early 1995. The dedication ceremony was attended by then Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, among other dignitaries. Secretary Babbitt used the occasion to sing the praises of private-federal partnerships, such as the CAM-BLM partnership that had created this interpretive site. The Secretary had had a short career as a geologist before going into law and politics, so he took an interest in the details of Frenchman Mountain's stratigraphic and structural history. Having learned that Frenchman Mountain had moved some 80 km to the west, from an area near the Arizona-Nevada border, in his dedication speech Mr. Babbitt, a former governor of Arizona, said that Arizona wanted Frenchman Mountain back. In my speech, which followed the Secretary's, I told the Secretary that Nevada was not willing to return Frenchman Mountain to Arizona, but that we were prepared to give them Yucca Mountain in exchange.

It was a good beginning. Those of us involved in this project were delighted that we had succeeded in attracting some attention to the previously neglected east side of the Las Vegas Valley, and we had prodded the BLM into adopting a more active management posture in the Frenchman Mountain area. Just possibly, our interpretive site might spark an interest in geology among some unsuspecting passers-by. Bare rock is such a conspicuous aspect of the local landscape that anyone with a kernel of curiosity about his or her surroundings should be easily drawn into the local geology. The site has been well visited (although we have no idea of how many visitors), and it has survived numerous acts of vandalism.

Phase II - The Interpretive Trail and Las Vegas Valley Overlook Panel

Phase II - The Interpretive Trail and Las Vegas Valley Overlook Panel

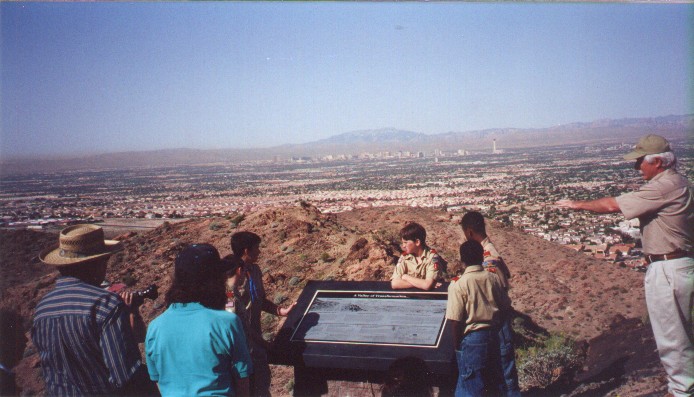

Shortly after dedicating the interpretive site we began to discuss the idea of a short interpretive trail that would lead from the site to an overlook point about ¼ mile away. The objectives of the trail would be to further engage visitors in the local geology, and to provide a new recreation opportunity close to the city. The route was to zigzag up a hill, going back and forth across the contact between the Tapeats Sandstone and the Precambrian basement complex. I flagged a few interesting rock exposures, including some on both sides of the Great Unconformity, and we arranged with Boy Scout Troop 133 to construct the trail connecting the flags. One scout orchestrated the construction of the trail as part of his Eagle community service project.

Shortly after dedicating the interpretive site we began to discuss the idea of a short interpretive trail that would lead from the site to an overlook point about ¼ mile away. The objectives of the trail would be to further engage visitors in the local geology, and to provide a new recreation opportunity close to the city. The route was to zigzag up a hill, going back and forth across the contact between the Tapeats Sandstone and the Precambrian basement complex. I flagged a few interesting rock exposures, including some on both sides of the Great Unconformity, and we arranged with Boy Scout Troop 133 to construct the trail connecting the flags. One scout orchestrated the construction of the trail as part of his Eagle community service project.

Five 8½" by 11" photometal interpretive signs were place along the trail. Each sign is glued to a commercially available, steel panel welded to a steel post. Each post was mortared into a hole drilled a few inches into the bedrock, supported by a pile of rocks mortared around the base of the post. The signs were very kindly prepared for us at no cost by the Nevada Division of State Parks. In general, the interpretive messages become progressively more abstract and complex the higher they are up the trail, however technical jargon is kept to a minimum. I endeavored to write the text in such way that any high school graduate could understand it. All but one of these trail signs are placed a step or two off the main trail, so that they are not obtrusive to the hiker who wants to enjoy the trail without tripping over signs.

Five 8½" by 11" photometal interpretive signs were place along the trail. Each sign is glued to a commercially available, steel panel welded to a steel post. Each post was mortared into a hole drilled a few inches into the bedrock, supported by a pile of rocks mortared around the base of the post. The signs were very kindly prepared for us at no cost by the Nevada Division of State Parks. In general, the interpretive messages become progressively more abstract and complex the higher they are up the trail, however technical jargon is kept to a minimum. I endeavored to write the text in such way that any high school graduate could understand it. All but one of these trail signs are placed a step or two off the main trail, so that they are not obtrusive to the hiker who wants to enjoy the trail without tripping over signs.

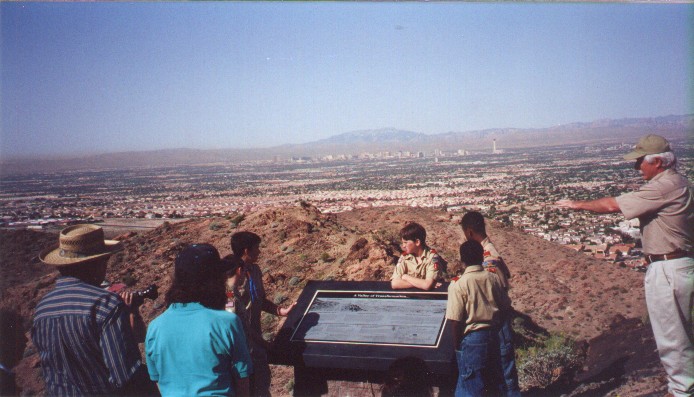

The trail ends at an overlook of Las Vegas Valley where another 24" by 48" stone panel provides the names of the major topographic features and summarizes the geologic evolution of Southern Nevada. This panel and the platform on which it sits were paid for by a federal recreational trail grant of about $5,000. The grant required a 50% local match, which was covered by in-kind services, mainly through donated design and construction help.

The trail ends at an overlook of Las Vegas Valley where another 24" by 48" stone panel provides the names of the major topographic features and summarizes the geologic evolution of Southern Nevada. This panel and the platform on which it sits were paid for by a federal recreational trail grant of about $5,000. The grant required a 50% local match, which was covered by in-kind services, mainly through donated design and construction help.

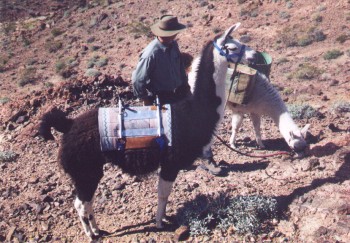

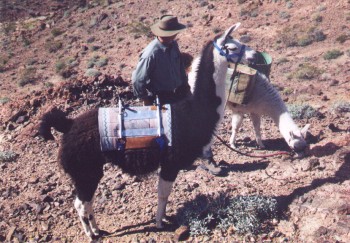

A major challenge was transporting materials to the overlook site, which is not accessible by motor vehicle. Concrete blocks, mortar, and water were transported to the site by llamas, courtesy of Danny and Vicki Riddle of Los Lauro Llamas. The wedge-shaped box into which the overlook stone panel is recessed is made of 3/16" steel. It was powder coated (a special painting process) for weather resistance. This steel box weighs at least 400 pounds. It was transported to the site on a specially built cart, pulled and pushed by several community service volunteers under the leadership of BLM volunteer coordinator Ed O'Sullivan. The 24" by 48" stone panel was transported to the site on a four-wheeled, flat-bed, garden cart.

The interpretive trail and overlook site were dedicated on April 13, 2001.

We decided to place two interpretive panels at this site. (Phase II had not yet been conceived.) One panel was located close to the road, and the other a short distance away directly adjacent to the exposure of the Great Unconformity. The panels, which were prepared by Stone Imagery of Carlsbad, California (StoneImage@earthlink.net), are coarse crystalline diorite from southern India (called "black granite" in the stone industry). The text and figures are etched into the stone. The result is a very attractive stone panel that stands up well to abuse and cleans up very well.

We decided to place two interpretive panels at this site. (Phase II had not yet been conceived.) One panel was located close to the road, and the other a short distance away directly adjacent to the exposure of the Great Unconformity. The panels, which were prepared by Stone Imagery of Carlsbad, California (StoneImage@earthlink.net), are coarse crystalline diorite from southern India (called "black granite" in the stone industry). The text and figures are etched into the stone. The result is a very attractive stone panel that stands up well to abuse and cleans up very well.

The roadside panel is inset into a tilted concrete platform mounted on a cinder block pedestal. This panel summarizes the geology of Frenchman Mountain and the Great Unconformity. Much of the text and most of the diagrams of both panels are included on this website. The stone panels were paid for with money raised by CAM from corporate sponsors and the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. A BLM crew prepared the site and built the platform and pedestal for the roadside panel. The outcrop panel was originally placed on a steel plate attached to a steel post. Vandals fairly quickly destroyed this outcrop panel, and the BLM replaced it with a new one mounted on a cinder block pillar. Unfortunately, the crew who built the new pillar apparently did not know exactly where the unconformity was located, and they didn't bother to ask. They oriented the new panel about 40º from where it should be facing. This confuses some visitors who don't know exactly where to look to see the Great Unconformity. As exemplified by the miss-alignment of the pedestal, poor communication and frequent staff turnover at BLM have been mild recurring problems in the CAM-BLM partnership. In general, however, the relationship has been friendly, efficient, and mutually supportive.

The roadside panel is inset into a tilted concrete platform mounted on a cinder block pedestal. This panel summarizes the geology of Frenchman Mountain and the Great Unconformity. Much of the text and most of the diagrams of both panels are included on this website. The stone panels were paid for with money raised by CAM from corporate sponsors and the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. A BLM crew prepared the site and built the platform and pedestal for the roadside panel. The outcrop panel was originally placed on a steel plate attached to a steel post. Vandals fairly quickly destroyed this outcrop panel, and the BLM replaced it with a new one mounted on a cinder block pillar. Unfortunately, the crew who built the new pillar apparently did not know exactly where the unconformity was located, and they didn't bother to ask. They oriented the new panel about 40º from where it should be facing. This confuses some visitors who don't know exactly where to look to see the Great Unconformity. As exemplified by the miss-alignment of the pedestal, poor communication and frequent staff turnover at BLM have been mild recurring problems in the CAM-BLM partnership. In general, however, the relationship has been friendly, efficient, and mutually supportive.

Shortly after dedicating the interpretive site we began to discuss the idea of a short interpretive trail that would lead from the site to an overlook point about ¼ mile away. The objectives of the trail would be to further engage visitors in the local geology, and to provide a new recreation opportunity close to the city. The route was to zigzag up a hill, going back and forth across the contact between the Tapeats Sandstone and the Precambrian basement complex. I flagged a few interesting rock exposures, including some on both sides of the Great Unconformity, and we arranged with Boy Scout Troop 133 to construct the trail connecting the flags. One scout orchestrated the construction of the trail as part of his Eagle community service project.

Shortly after dedicating the interpretive site we began to discuss the idea of a short interpretive trail that would lead from the site to an overlook point about ¼ mile away. The objectives of the trail would be to further engage visitors in the local geology, and to provide a new recreation opportunity close to the city. The route was to zigzag up a hill, going back and forth across the contact between the Tapeats Sandstone and the Precambrian basement complex. I flagged a few interesting rock exposures, including some on both sides of the Great Unconformity, and we arranged with Boy Scout Troop 133 to construct the trail connecting the flags. One scout orchestrated the construction of the trail as part of his Eagle community service project.

Five 8½" by 11" photometal interpretive signs were place along the trail. Each sign is glued to a commercially available, steel panel welded to a steel post. Each post was mortared into a hole drilled a few inches into the bedrock, supported by a pile of rocks mortared around the base of the post. The signs were very kindly prepared for us at no cost by the Nevada Division of State Parks. In general, the interpretive messages become progressively more abstract and complex the higher they are up the trail, however technical jargon is kept to a minimum. I endeavored to write the text in such way that any high school graduate could understand it. All but one of these trail signs are placed a step or two off the main trail, so that they are not obtrusive to the hiker who wants to enjoy the trail without tripping over signs.

Five 8½" by 11" photometal interpretive signs were place along the trail. Each sign is glued to a commercially available, steel panel welded to a steel post. Each post was mortared into a hole drilled a few inches into the bedrock, supported by a pile of rocks mortared around the base of the post. The signs were very kindly prepared for us at no cost by the Nevada Division of State Parks. In general, the interpretive messages become progressively more abstract and complex the higher they are up the trail, however technical jargon is kept to a minimum. I endeavored to write the text in such way that any high school graduate could understand it. All but one of these trail signs are placed a step or two off the main trail, so that they are not obtrusive to the hiker who wants to enjoy the trail without tripping over signs.

The trail ends at an overlook of Las Vegas Valley where another 24" by 48" stone panel provides the names of the major topographic features and summarizes the geologic evolution of Southern Nevada. This panel and the platform on which it sits were paid for by a federal recreational trail grant of about $5,000. The grant required a 50% local match, which was covered by in-kind services, mainly through donated design and construction help.

The trail ends at an overlook of Las Vegas Valley where another 24" by 48" stone panel provides the names of the major topographic features and summarizes the geologic evolution of Southern Nevada. This panel and the platform on which it sits were paid for by a federal recreational trail grant of about $5,000. The grant required a 50% local match, which was covered by in-kind services, mainly through donated design and construction help.